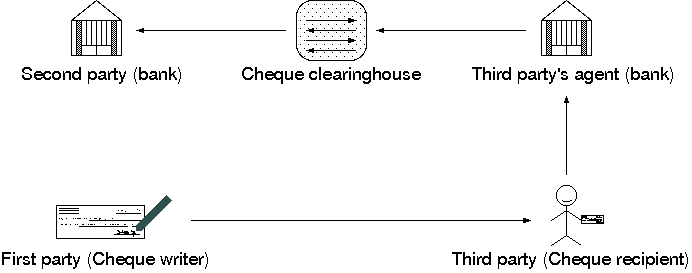

Figure 1: A cheques's travels

A cheque is a token created by a first party (cheque writer) addressed to a second party (bank) which authorizes and requests the second party to disburse money to a third party (cheque recipient) or agent thereof.

What's wrong with that? Well, simply that the token reaches its addressee in such an indirect way.

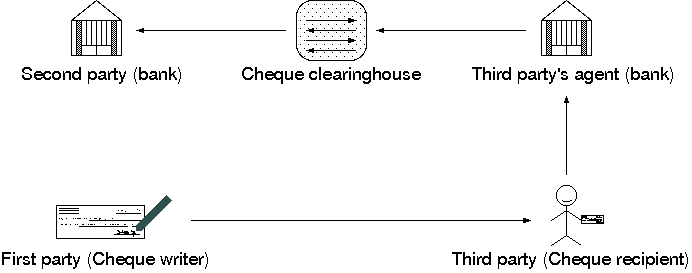

Figure 1: A cheques's travels

If I write a cheque, I am writing instructions intended for my bank. They say “Please pay to the order of” and continue by naming the intended recipient and amount of money. They request that this money be taken from the funds that they are holding on my behalf (the contents of my bank account). My bank will receive those instructions and follow them.

But if this document contained instructions for my bank, then why did I give it so somebody else rather than to my bank? If I have instructions for my bank regarding the handling of my money, I want to give those instructions as directly as possible to my bank, and more importantly, I don't want my bank to be taking and following instructions regarding the disposition of my money from anyone but me or whomever I authorize ahead of time to act on my behalf. By giving them to the money's intended recipient I am making the very complicated request, “please tell your bank to tell my bank that I said they could take money out of my account and give it to you”. I would much rather say to my bank, “please take money out of my account and give it on my behalf to the following person”. Since I have an established relationship with my bank we can agree between us ahead of time how such requests should be received, how thouroughly they should be authenticated, and how much the service that the bank is offering me should cost me.

The greatest problem in principle with the cheque process is a conflict of interest. It is very important for the instructions contained on a cheque to be delivered to my bank unchanged from the way I wrote them. The party who stands to gain the most by corrupting those instructions is the intended recipient of the money. And yet the instructions pass right through that person's hands. I call this a problem in principle because cheques are designed with features to prevent this kind of fraud, and furthermore, such fraud is easy to detect after the fact via the audit trail. Nevertheless, security features on cheques are not really all that great, and it is not wise from a security point of view to rely on tamper resistance so completely as to endorse sending the instructions through a completely untrusted path.

A second reason why the cheque compensation chain does not work well it that my bank, to whom the disbursement request is being made, has limited power to ensure that the request is obeyed correctly. All cheques except cheques made out to cash or to the bearer are requests to disburse money, but only to a specific third party. As the executor of the cheque writer's wish, it should be the responsibility of my bank to obey the instructions correctly. Unfortunately, by the time they receive the request, it is coming from (typically) a compensation clearinghouse two or more degrees removed from third party. They have no way of authenticating that it is indeed the correct third party who is attempting to receive the funds.

While I do not know this to be true, I shall assume that all of the various financial institutions who exchange compensation requests with each other, through a compensation clearinghouse or directly, have mutually agreed to verify the identify of persons depositing or cashing cheques before acting as an agent on behalf of those persons and presenting the cheques to each other for compensation, that they trust each other to do so,and that these agreements are binding and possibly even legislated. Nevertheless, the cheque writer is forced to rely on agreements made by someone else, and to trust all of these financial institutions transitively, a requirement that should not exist. For the first party (cheque writer) to be a customer of one financial institution may require that the first party trust that particular financial institution, but should not require anything further.

The foregoing arguments do not imply that I am personally especially afraid or cheque forgery or misbehaviour by a financial institution. Certainly most kinds of forgery or tampering run the risk of discovery after the fact even if they are successful, and financial institutions, at least in Canada, are subject to comprehensive audits to a greater extent than most other corporations, and misbehaviour is considered scandelous enough when it is discovered that it is not likely to occur often. Yet this is not a reason to select a compensation model with inferior security. Moreover, there are additional issues with this model that have practical implications in addition to security implications.

The first of these is that the feedback loop for cheque compensation is very long. Although electronic cheque processing quickens the discovery of problems such as insufficient funds, the physical token must still travel through the steps shows in figure 1. This process takes time, and it means that one can never be sure whether a cheque has actually cleared until many days have passed. Then, if a problem is discovered, the cheque is rejected and the chain is followed in the reverse direction. For a cheque that could not be compensated to make it all the way back to the cheque writer, a delay of half a month is actually typical.

Even worse, there is no positive acknowledgement given to the third party (recipient of the funds) when the cheque has been successfully compensated. It is necesary to wait for a timeout and assume that the compensation was successful afterwards.

Cheques are thus authenticated tokens that are sent along an indirect path through unknown third parties instead of directly to the addressee along the path of an established trust relashionship, they require the writer to trust such unknown parties to treat the instructions on the cheque correctly, they introduce delays because of the long indirect path, and there is a lack of feedback to the end users about the status of their compensation.

Direct withdrawls are another completely flawed and insecure way of exchanging money. I am talking about the feature that some companies offer to their customers to have payments to this company withdrawn directly from the customer's bank account.

A direct withdrawl request means this: “Please transfer money from the bank account whose identification is given herewith to me. I state that the owner of this bank account has authorized me to transfer this money.”.

That is a lot like a cheque in that the bank where the account in question is located is going to receive this request from a third party who may or (most likely) may not be their customer. They will probably even receive this request even more indirectly from an intermediate clearinghouse (just like with cheques). But that's where the similarity with cheques ends. In this case the instructions were not even issued by the holder of the bank account. They were issued by the recipient of the money. Although the recipient is supposed to have received consent from the account holder to issue these instructions, the bank has no way of knowing whether this is true and in fact will never receive any authenticated followup confirmation that the instructions were valid at all. And yet this bank will simply obey the request and disburse the money.

Let me state that again: some random third party can submit electronically to their bank a direct withdrawl request which contains my bank account number and a given amount of money, and they will receive this money out of my account without my even being consulted. The only thing that stands in the way of this kind of fraud is my consciencious verification of every transaction in my bank account (and I might miss it), spot checks performed by humans at the bank (but the large majority of transactions are not subjected to these).

Banks need to develop user interfaces that allow customers to send money from their accounts to arbitrary recipients. The recipients can be identified by their bank and account number or some other way.

Some banks in Canada have made an effort to implement such user interfaces. Five Canadian banks offer Interac Email Money Transfers. Unfortunately this method is extremely limited. It can only be sourced from the five participating banks, the service changes are quite high, and there are low daily limits on the amount of money that can be transfered. Also, because the recipient is named by email address and not by account number the sender and recipient must agree out of band on an authentication token. If they had coupled the use of email with PGP then this problem would not have presented itself. Worst of all, at least in the case of one of the participating banks with which I have experience, some types of bank accounts can neither send nor receive Interac Email Money Transfers, and the only suggestion offered is to use a different account! On the plus side, Interac Email Money Transfers are quick (but not instantaneous: you have to wait for an email to arrive which I have seen take a few hours) when transferring both to and from a participating bank.

In the meantime while waiting for the industry to develop a reasonable process, one can use a service such as hyperWALLET to actually move the money. These services enable instant transfers from one account holder to another with no hassle. The problem, for the purpose of using these services as proxies for transfers from one bank account to another, is, of course, getting money into them from a bank account and getting money out of them into a bank account. PayPal could have been another example except that they do not actually solve the problem of funding the account securely: they rely on direct whthdrawl to get money from a bank account into a PayPal account. As indicated above, direct wihthdrawls are even more insecure and illogically conceived than cheques. hyperWALLET, on the other hand, does solve the problem. It relies on banks' existing bill payment services to get money into hyperWALLET, and direct deposit to get money out.

Because hyperWALLET has solved the problem of relying on insecure banking processes to transfer money, and also because they have improved their service even more by forming partnerships with over 200 credit unions (reference) so that transfers of funds from accounts at those credit unions are even more convenient and faster, I recommend hyperWALLET as a viable alternative to the nonsensical concepts of cheques and direct withdrawl, until the banks come up with something better. What's more, it takes less time to fund a hyperWALLET account and send those funds back out to another bank account than it does for a cheque to clear, and much less time than the same operation using PayPal.